When a delivery truck rolled into Long Island this past April, it seemed like just another ordinary workday. But as one employee inspected the vehicle after its 700-mile journey, they heard something unexpected — the faint sound of chirping coming from the back.

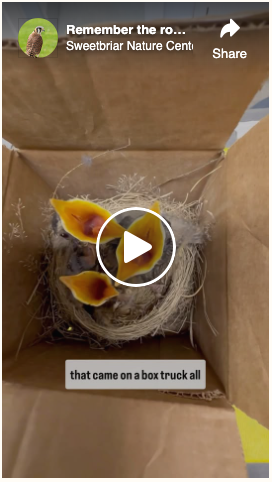

Peering closer, the worker spotted a fragile nest wedged behind the underride guard of the truck. Inside were three tiny baby birds, alive but dangerously exposed after their long and bumpy ride.

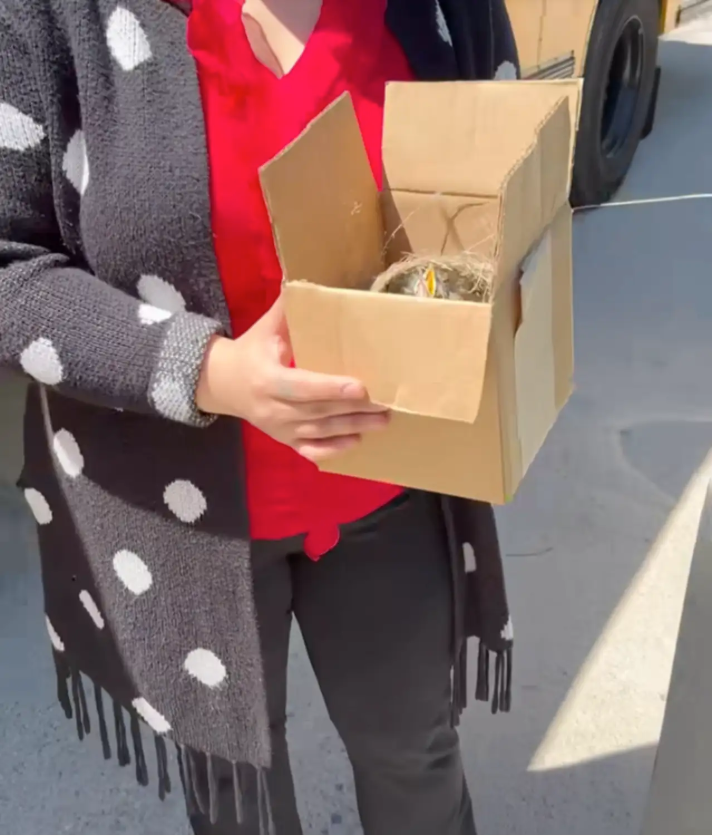

Unsure what to do, the employee turned to Nubia Villatoro, an executive assistant at the site known for her compassion toward animals.

“The nest was not secured whatsoever,” Villatoro told The Dodo. “I honestly don’t know how they stayed in there.”

Villatoro could see the babies desperately calling out for food, their mouths wide open. Remembering a field trip she’d once taken, she knew exactly where to turn: Sweetbriar Nature Center, a licensed wildlife rehabilitation center nearby.

When Villatoro arrived with the unexpected passengers, Janine Bendicksen, director of wildlife rehabilitation, could hardly believe their story. “I thought, ‘There’s no way they made it through 15 hours on the road without food or water,’” she said.

Against all odds, the babies — just under two weeks old — were in “surprisingly good” condition. They turned out to be robins, Sweetbriar’s very first robin nest of the year.

Only federally licensed wildlife rehabilitation centers, like Sweetbriar Nature Center, are allowed to care for migratory birds, including robins. Bendicksen noted that usually they get a heads up before animals come in, but Villatoro wasted no time transporting the robins to the center. After hearing their remarkable story, “There was absolutely no way we could say no to these babies,” Bendicksen said.

While it’s not the first time baby birds have arrived at Sweetbriar after accidentally hitching a ride, it’s definitely the farthest a nest has traveled with its occupants inside. Bendicksen credits their survival with the robin’s hardy disposition. “I just think that they're built to survive in a way,” she said. “They're a little stronger than most.”

Still, she was surprised they’d lived through such an ordeal.

These babies were the center’s first robins of the year. Further south, robin babies had already started hatching, but it was still too early in the season up in New York. This meant plenty of staff available, which is necessary with baby birds.

Staff immediately placed the chicks in a warm incubator and began a strict feeding schedule: every 30 minutes from sunrise to sunset. As the weeks passed, the babies grew stronger, learning how to perch, flutter, and eventually peck at earthworms and bugs on their own.

“One day, they just decide, ‘I’m done with you. I don’t want food from you anymore,’” Bendicksen explained with a laugh. “That’s how we know they’re ready for the aviaries.”

After four weeks of round-the-clock care, the once-delicate nestlings had transformed into strong young robins, ready to take on the world. On a sunny afternoon at the end of May, staff gathered as the trio was released back into the wild.

“The release criteria is simple — they have to be self-sufficient, and the weather has to be right,” Bendicksen said. “And off they go.”

Villatoro later watched Sweetbriar’s video of the release and admitted it brought tears to her eyes. “They get to live their lives,” she said softly.

For Sweetbriar staff, the robins’ survival was nothing short of remarkable — not only had they endured an exhausting journey clinging to a nest on a moving truck, but they’d also beaten the odds stacked against such fragile creatures.

The center continues to leave food out in case the robins return, just as their wild parents would. So far, there’s been no sign of them — which, Bendicksen noted, is the best outcome of all.

“They’re out there living as wild birds should,” she said.

To learn more about Sweetbriar Nature Center or support their work, you can visit their website.