One summer day in July, Julie Bernstein glanced out her window in Pennsylvania and immediately knew something was wrong.

A large red fox was wandering through her backyard — but wrapped around his neck was a strange piece of tubing. It looked heavy, awkward, and dangerous. Bernstein worried that if it wasn’t removed, the fox could eventually starve, get injured, or worse.

Unsure what to do, she contacted Aark Wildlife Rehabilitation and Education Center for guidance. At their suggestion, she also set up a trail camera to keep track of the fox’s movements and assess the situation more closely.

The tubing appeared to have split into two rigid pieces, with the fox’s thick fur poking out between them as he moved across the yard.

“The object around his neck was likely a section of drainage pipe,” Amanda Leyden, a licensed wildlife rehabilitator and clinic director at Aark, told The Dodo. “Small animals sometimes take shelter in these pipes, and a curious fox may stick its head inside to investigate or hunt, only to get stuck when trying to back out.”

Aark explained that the safest way to help the fox would be to humanely trap him and bring him in for care — a process that would require patience and precision.

Bernstein began by setting up a feeding station in an area the fox frequently visited. She affectionately named him Tubey and carefully documented his habits with the trail camera.

Once Tubey felt comfortable, Bernstein placed a humane trap nearby — close enough to notice, but not close enough to raise suspicion. Then, day by day, she slowly moved the food closer to the trap, encouraging him to follow his meal inside.

“Foxes are extremely intelligent and cautious,” Leyden said. “So this process took quite a bit of time and patience.”

Nearly three months later, in late October, Bernstein finally received the moment she’d been waiting for: Tubey had entered the trap. She acted immediately, transporting him to Aark’s facility for help.

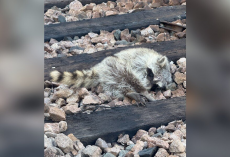

Despite everything, Tubey was in surprisingly good condition.

“He had a beautiful, full coat and weighed over 18 pounds,” Leyden said. “He was a very large, healthy red fox.”

Still, the pipe around his neck had likely been uncomfortable for a long time, and being confined and surrounded by people was understandably stressful.

Aark’s veterinary team gently sedated Tubey, carefully cut away the tubing, and examined his neck for injuries.

To everyone’s relief, there were no wounds beneath his thick fur — just a few ticks, which were promptly removed.

As a precaution, the team also tested for sarcoptic mange, a potentially fatal parasitic disease that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service says could be fatal if left untreated. Tubey’s results came back negative.

“Once Tubey woke up fully from sedation, he appeared noticeably calmer,” Leyden said. “He settled comfortably in his crate, alert but no longer panicked.”

Leyden also used the opportunity to remind people how small actions can prevent situations like this.

“Covering open drainage pipes with hardware cloth and cutting up plastic rings can make a real difference,” she said. “We often see wildlife tangled in packaging or containers that could have been safely discarded.”

With the tube finally gone, Bernstein returned Tubey to the spot where she’d first seen him. The fox paused for just a second — then dashed out of the crate and back into the woods, free at last.

To support rescues like Tubey’s, you can donate to Aark Wildlife Rehabilitation and Education Center or purchase items from their wish list through their website.